Around the middle of The Rift, a sister who insists that her traumatic twenty-year disappearance came about because she woke up in another world says, by way of explaining why she now shelves her novels in with her non-fiction, that “no book is completely true or completely a lie. A famous philosopher at the Lyceum once said that the written word has a closer relationship to memory than the literal truth, that all truths are questionable, even the larger ones. Anyway, it’s more interesting. When you shelve books alphabetically you stop noticing them, don’t you find?”

I may be too time-poor to even contemplate such an almighty organisational endeavour, and yet… I’m tempted, because there’s some truth to Julie’s attitude, I’m sure. Once something becomes known, you do stop noticing it—and there’s so much in the world that needs noticing, so much that in a sense deserves the extra attention. Not least Nina Allan’s new novel, which, like her last—namely The Race, a story of stories about the lives of ordinary people becoming unfastened from reality—mixes the real with the unreal to tell a uniquely human tale, albeit one that may contain aliens.

Like the lawless library we learn about later, The Rift swiftly resists the rules readers expect fiction to follow from the first by beginning both before and after the fact. Before, we learn of a girl—Julie’s little sister Selena—who befriends a bloke who sadly commits suicide when his koi pond is poisoned. After, the girl is a grown-up, out drinking with a few of her few friends, who answers the phone upon coming home to hear a woman introduce herself as Julie:

Selena’s first, split-second reaction was that she didn’t know anyone called Julie and so who the hell was this speaking? The second was that this couldn’t be happening, because this couldn’t be real. Julie was missing. Her absence defined her. The voice coming down the wire must belong to someone else.

But it doesn’t. The caller is her missing sister. Selena knows it in her bones from the moment they meet in a coffee shop a day later. She has the same way of making Selena feel insignificant; the same memories of what they went through when they were wee; she keeps the same secrets, even.

She keeps a couple of other secrets too, to start. Even after Selena accepts this new though not necessarily improved Julie into her life—a quiet life defined by Julie’s absence as much if not more so than Julie’s own—she simply won’t tell her sister where she’s been all these years, nor why she’s gotten in touch all of a sudden.

Julie’s reticence to speak about her experience rings any number of alarm bells in her sister’s head, but Selena is so relieved to have her back that she wonders whether or not knowing the truth of whatever hell Julie has been through is necessary. “Perhaps it was better to remain in the dark about what had happened,” she tells herself. “There was an argument for not pursuing it, for ignoring the fork in the road, and moving on.” But the truth, inconvenient as it may be, unbelievable as it sometimes seems, will out:

On Saturday July 16th 1994, I travelled from the area of woodland around Hatchmere Lake, near Warrington, Cheshire, to the shore of the Shuubseet, or Shoe Lake, an elongated, slipper-shaped stretch of water not far from the western outskirts of Fiby, which is the smallest and most southerly of the six great city-states of the planet of Tristane, one of the eight planets of the Suur System, in the Aww Galaxy.

How I came to be there I cannot tell you. Cally’s brother Noah believes there is a rift—a transept, he calls it—something like an enlarged pore in the void between Earth and Tristane that allows objects and occasionally people to travel instantaneously from one place to the other.

We’re treated to a Julie’s-eye view of her time on Tristane in the company of Cally and Noah in The Rift‘s second section: a subtly surreal and somewhat sinister story about a young woman trying and invariably failing to fit in in a new world punctuated—as is the rest of the text—by interstitial excerpts of poems, encyclopaedia entries, newspaper reports and erotic novels, some of which are apparently factual whilst others are fabricated from the fantastical. Amidst all this is a detail Julie seems ill at ease with, concerning a man with a van she only narrowly escaped from before she awakened elsewhere.

Here, then, The Rift is quite literally riven, in that this extended interlude divides Selena’s account just as Julie’s strange tale splits the relationship she’s reestablished with her sister down the middle. Symbolically, this is a successful step in the structure of the story’s stairs; narratively, alas, much of the middle acts lacks. Tristane feels so weightless, and Julie’s recollection of her magical vacation there so shapeless, that it all comes off as false.

And perhaps it’s supposed to. Selena clearly doesn’t believe in this other world either, dismissing it as “a delusion of some kind maybe, a fugue state, brought on by her experience in the van with Steven Jimson.” But neither can Selena “bring herself to believe that Julie was simply lying to her, that she had concocted this ridiculous story as—as what, exactly? An excuse for what she’d put them all through? […] On the whole, the idea that Julie had gone mad was a lot less painful.”

Mad she may be—and there is admittedly a bit of family history that supports Selena’s suspicion—but believe it or not, Julie’s truth is what it is. You can take it at face value or fashion a frame of fact around it. But what exactly makes a fact that, Allan asks.

In The Rift‘s last act the aforementioned interstitials come thick and fast, foregrounding the fine line between tall tales and truths. One concerns the Wels Catfish, a “placid and slow-moving” species of beast found throughout the UK and Europe; another gives us the Gren-Moloch, “a fearless, rapacious predator” sometimes seen in the saltwater of Tristane’s Marilly Sea. If we put aside our preconceptions, both of these creatures are either perfectly credible or perfectly incredible. Perspective is the only reason we accept one definition and dismiss the other out of hand.

And so we circle back to the seemingly disorganised library we began with. In this, as in everything in The Rift, it’s up to us to to decide what to pay attention to and what to ignore; what to take on faith and what to doubt. One thing you won’t find in this brilliantly ambiguous book is the truth, but so long as you don’t read it expecting a definitive explanation, you definitely won’t be disappointed.

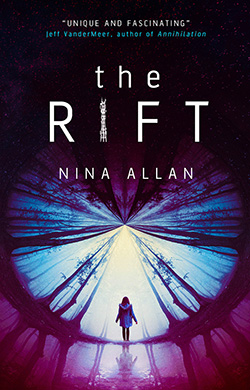

The Rift is available July 11th from Titan Books.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He lives with about a bazillion books, his better half and a certain sleekit wee beastie in the central belt of bonnie Scotland.